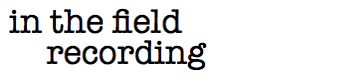

The Lotería de la Migración reimagines the traditional “Mexican Lottery” card game as a lens through which to view issues surrounding Central American and Mexican migration north to the United States. While working in San Salvador, and Tapachula, Chiapas, near Mexico’s border with Guatemala, I was struck by the way in which people’s desperate effort to escape El Salvador and Honduras morbidly resembled the children’s board game Chutes and Ladders, or a video game, one in which migrant refugees battle innumerable logistical, political and criminal obstacles, only to be bounced back to square one to start over. It is a journey that has become increasingly dangerous and inhumane, one that showcases the brutal hypocrisy of US policy and leaves thousands of dead literally littering the trail north. Although I began this project when there were still more than a dozen white men vying for the Republican nomination in the 2016 presidential election, the rise of Trump and his xenophobic and racist immigration and refugee policies continues to inspire and add urgency to it.

A game that has been played throughout the region for more than one-hundred and fifty years, Mexican Lottery is quite similar to our Bingo: cards are drawn at random from an iconic deck of 54 images, but rather than announcing their numbers, the master of ceremonies calls out their names or alludes to them with either improvisational or well-established, traditional snippets of verse: El Valiente, the Courageous, with knife and serape in arm; El Nopal, the culinary cactus of Mexico; the Watermelon; the Hand; the Skull. Each player has before them a 4 x 4 grid of the pictures, known as a tabla; games are won by matching a row of four, filling in all the corners of the card, or completing some other pre-determined pattern.

The most famous version of this game is the Don Clemente deck, mass-produced by Pasatiempos Gallo, but there is a long tradition of variations and alternate imagery, including one created by the great Mexican graphic artist José Guadalupe Posada. The images are cultural touchstones, a kind of regional Tarot of Mexican and Central American iconography, and in fact various systems have been devised to use lotería cards for divination. The Lotería de la Migración takes the bold, posterized colors of the historic deck as a point of departure for confronting various heinous aspects of the migration question. Some of the cards directly reference the Don Clemente deck; others do not. Once complete, the project will be published as a deck of playing cards.

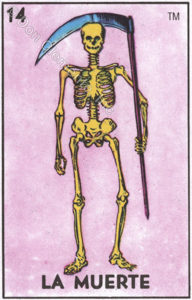

(The smaller images are examples from the Don Clemente deck, reproduced here without permission.)

THIRST: In 2008 Daniel Millis of Arizona was found guilty of littering by a federal court after the US Fish and Wildlife Service ticketed him for “disposal of waste” when he admitted to placing jugs of drinking water along known immigrant pathways through the desert south of Tucson, one of the deadliest migrant corridors in the United States. Two days earlier he had discovered the body of a fourteen-year-old El Salvadoran teenage girl, Josseline Hernandez, along the same trail. After two appeals, his conviction was overturned by the 9th Circuit in San Francisco largely because, according to the court, the law “is ambiguous as to whether purified water in a sealed bottle intended for human consumption meets the definition of “garbage.”

A dissenting judge in the case, Jay S. Bybee, wrote: “I would hold that Millis littered on a national wildlife refuge, and would affirm his conviction.” Bybee is perhaps best known for signing the memoranda authorizing the use of tortures (euphemistically described as “enhanced interrogation”) in the Bush-era “War on Terror.”

LA PALETA/THE POPSICKLE: For the migrant who has battled so many other obstacles and finally reached the U.S., Immigration and Customs Enforcement represents a last, ongoing and existential threat to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. With a 2024 budget of more than 8 billion dollars and 20,000 employees in 47 countries, I.C.E. is already the largest of our law enforcement agencies. President Trump has promised to greatly enlarge it.

Despite its size, I.C.E., as represented by its union, the National ICE Council, seems to have felt that pre-Trump their mandate was not taken seriously in Washington. In 2016, for the first time in its history, they endorsed a presidential candidate.

His reelection in 2024, and the ongoing expansion of I.C.E.’s power, brings uncertainty and fear to an unfair but stable system. No longer can good, hardworking migrants without legal status assume that they are secure so long as they keep their heads down and their noses clean. Already, families have been split apart and pillars of their communities deported, often to the shock and horror of neighbors professing to be Trump voters. The agency now operates with little oversight, and its victims, whether U.S. citizens or not, have little recourse.

MEDICAL ASSISTANCE: Both in Mexico and the U.S., migrants who are wounded or sick often risk their lives when they avoid seeking medical help. In the desert borderlands, people have almost certainly died of dehydration after hiding from CPB officials instead of requesting water. Fear of identification and deportation inspires deadly decisions to postpone medical care.

Obama-era policy number 10029.2, outlined in the “Enforcement Actions at or Focused on Sensitive Locations” memo, included hospitals on a list of environments and situations where ICE agents should avoid operating without special approval. In the Trump era, in-line with a general unleashing of ICE, this policy is much less clear.

In February, 2017, agents removed an El Salvadoran woman with a brain tumor from Huguley Hospital in Fort Worth, TX, and placed her in detention. In June, ICE staked out the Arizona desert camp of “No More Deaths,” an aid organization that offers free water and medical assistance to migrants. Serving a warrant, ICE arrested and removed four men who were receiving emergency medical care. According to the New York Times, “the agency had previously abided by an informal, Obama-era agreement allowing migrants to seek medical help at the camp without fear of arrest.”

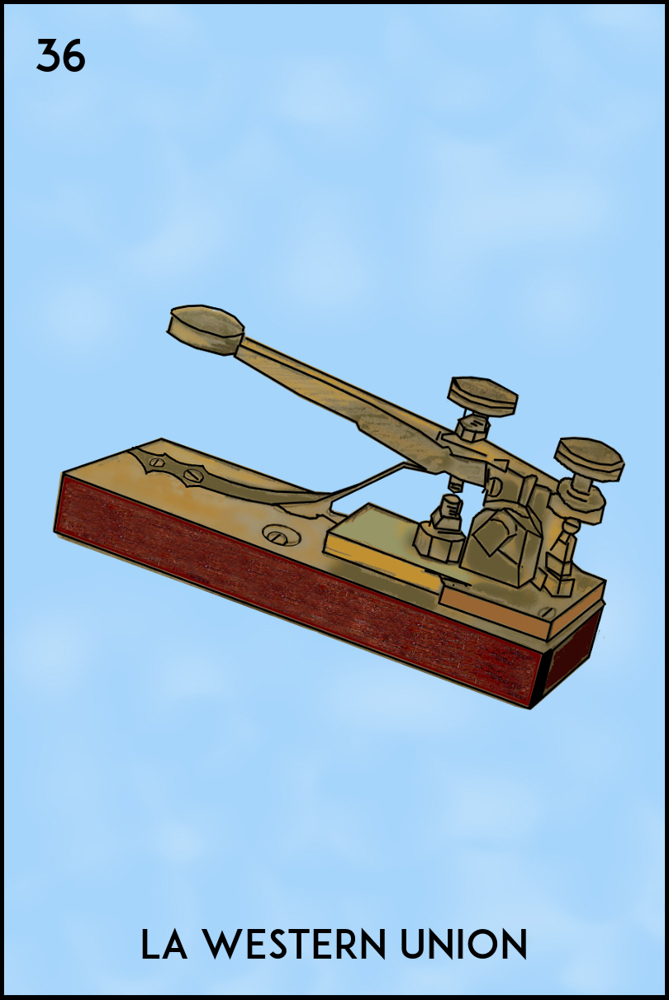

REMITTENCE PENALTIES: Western Union, which once had a near-monopoly on long-distance communication, has with the rise of the internet and the decline of the telegraph era reinvented itself as a company with a near-monopoly on money transfer and remittence. Migrants, kidnappers and extortionists alike use the service to receive funds from relatives, or the relatives of their victims. The company’s exorbitant rates make them a top-level predator in the food-chain of the financial exploitation of migrants. As David Romero has pointed out, remittences comprise such a vast tranche of the GDP of many “southern” American countries that governments from Kingston to Montevideo should sensibly absorb any transaction costs in the interests of their own economies. Instead they stand by while Western Union rakes off as much as 19% of each tiny, desperate transfer. In some cases, as for instance with the $1.50 per transaction charged in Haiti, governments even add their own spurious fees. All the length of Mexico migrants sit stranded for days and weeks waiting for friends and relatives in El Norte to assemble the funds to help them on their way.

SANTA MUERTE: The Santa Muerte, or “Sacred Death,” is a folk saint whose popularity has exploded over the last two decades. Also known as “La Flaca,” the skinny one, she is the patroness of drug traffickers, extortionists and migrant travelers alike. She “does not discriminate.” She is a powerful one-stop shop for spiritual intervention; her faithful followers ask her for help with everything from love and health to money and their safe arrival in the United States.

Would-be migrants may light a gold candle, representing prosperity, on the eve of the journey, and recite the traveler’s prayer to the Santa Muerte:

Santa de los caminos y mares,

Señora protectora y guardiana,

de los que vamos en camino,

no dejes que la fatalidad llegue

para interrumpir mi camino.

Cuida mis pasos en sendas desconocidas,

aleja a aquellos que dañan y despojan.

Ilumina mis pasos para marcar la senda correcta,

así los que atrás vienen

verán huellas y podrán evitar arraigos

que enferman y matan.

Saint of roads and seas,

Lady of protection and guardian

Of those of us who undertake the trail

Don’t allow fate to arrive

And interrupt my journey.

Guard my steps on unknown pathways

Keep far away those who would wound or rob.

Light my steps to indicate the proper path,

So that those coming behind

Will see traces and be able to avoid impediments

That sicken and kill.

Read R. Andrew Chesnut’s Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, The Skeleton Saint for more on La Flaca, and to find a longer version of the traveler’s prayer. This Santa Muerte statue was in a botánica in Tapachula, Chiapas.

THE RAFT: The Mexico-Guatemala border across the Suchiate River is a major passage on the route north from Central America. The two countries’ official border posts, at either end of a sleepy concrete bridge, see little traffic, but just upstream a constant flow of balsas cross back and forth with evident impunity. Basic watercraft fashioned from simple decking lashed to two giant truck or tractor tire inner tubes, they are poled across the river with long staffs. Piles of them are lashed and stacked on the banks.

Thanks to exchange-rate based arbitrage, staple goods like rice, Pepsi-cola, tomato paste and cornmeal are cheaper in Mexico; all day long rafts heavily laden with sacks and crates and trays of fresh fish set out from the thriving markets of Ciudad Hidalgo on the Chiapas side. At the river beach in Guatemala these are loaded in plain view into battered pickup trucks, before the rafts reload with human cargo; primarily Hondurans and Salvadorans fleeing their failed states, but one also meets entire families from Haiti, posses of young Senegalese adventurers, visa-less Chinese, Bangladeshis, Cubans and many others. The business of moving people here is entirely out in the open, and is a major source of profit and employment on both sides. Semi-officially, the place is called El Paso del Coyote, coyote being the slang term for human trafficker. A one-way trip on a balsa costs forty Mexican pesos, or about two dollars. Those who have no money at all simply wade.

Historical Exhibitions:

Lotería de la Migración and the Visual Languages of Advocacy

April 19th through May 31st, 2018

GIAF 2017, the Governor’s Island Art Fair.

The Other Side: A Swipple Reunion

A group show at ATLAS Newburgh, NY from April through June of 2017

A set of 5 images from the Lotería are now available as postcards, produced for sale in the gift shop at the Governors Island Art Fair. I have a few sets left, and all proceeds go to benefit organizations working in immigrant advocacy, security, health or legal aid. More details HERE.